@01:44 GMT

Position: 38° 26.997 N x 40° 37.743 W

Speed: 7 kts

Course: 104° True

Those were the words that came out of my mouth in the middle of the night – or was it early this morning – when Lauren woke me, to tell me that the A3 was coming unfurled, the auto-pilot was crunching again, and, of all things, there was a live bird on deck. I suppose it was an attempt at a “spin” on when it rains it pours, the best I could do with not enough sleep and some challenges ahead.

I had to be convinced to write this blog. When we set sail, we discussed being transparent about what was happening on board. The good and the bad. That message is a key component of our One More Step Challenge – things won’t always be perfect, you may not even achieve your goal, but what is important is that you’re trying to live a fuller life, with the necessary safety measures in place. Now it’s time for me to practice what I preach. And the flapping of the partially furled spinnaker is a constant reminder of the current situation on board.

My first instinct was to keep everything going on out here today quiet for a few reasons. I don’t want to worry family. I don’t want my seamanship skills to be questioned by some of the sailors I know are following. I was reminded by some of my crew though, that part of sailing is overcoming the inevitable obstacles that will come with any extended voyage. Anyone attempting this type of journey is bound to look back and realize that other choices could have been made before things went wrong. The important elements are: the crew is safe, the boat is secure, and we are barreling towards our destination with the sails we have left. More on that later.

The past 24 hours have really made me reach for my gran’s inspiration, “I can and I will.” In reality, this sea story started a few days ago, when, (as tends to happen in a sea story) I was woken in the middle of the night by Emily. “The wind is swirling and the boat is going in circles.” I was immediately alert and came on deck. Greg was at the helm and I asked him if he could steer by hand. “Yes.” Well, that meant that the auto-pilot, even though it said was engaged, was not. Hence the boat going in circles. Greg grabbed the wheel and got the boat under control. Luckily we had been motor-sailing under the main only, with no headsails.

Next we woke Lauren, who had to move out of the way for us to access the auto-pilot motor and chain. When I took down the panels, some screws and washers fell down. Ah – the nut holding gear for the chain had backed itself off and the chain had disengaged. After looking at our spare motor onboard as an example, Greg was able to resolve the problem. Everyone stood down and the normal watches continued.

Fast forward to yesterday. At some point we noticed a “clunk clunk” when the auto-pilot was engaged and the wheel seemed to skip. Another peek at the auto-pilot revealed that the chain was loose, so when a lot of effort was needed to steer, a gear or two would skip. Hand steering would now be required intermittently.

As predicted throughout the morning, the winds were slowly building as were the seas. The current sail configuration was full main and A3, our largest spinnaker. I have been gradually building my confidence in using this sail, testing its limits for the wind speeds that it – and my nerves – could handle. We have many more miles to voyage this year and this sail is a key part of the wardrobe. The biggest consideration was the difficulty to bring the sail down, once winds got too high. This spinnaker does have a sock that is used to snuff it, before then lowering it to the deck for stowage.

As the winds continued to be above 20kts sustained, I made the call. “Lauren, go wake Rudy and douse the A3.” They got into life vests and clipped in on the foredeck. Rudy wore the headset we use to communicate from the foredeck to the helm. “Ready?” I asked. “Yes” came the reply. I headed the boat downwind to reduce the pressure on the sail and began easing the sheet. Lauren began to haul away on the line used to pull the sock down. She stopped suddenly, noticing a knot in the line. It’s a continuous loop, so if the knot reached the sock before the sock was down, we wouldn’t have been able to continue to douse it. Lauren worked to untangle the knot – and then everything happened.

The sail wrapped itself quickly around the forestay, twisting and twisting around the jib that was already furled there. I sent Lauren to wake Emily and Greg, who were off watch, to come help. Meanwhile, the auto-pilot had again decided to complain, leaving me to need to split my focus between steering and helping the crew resolve the problem.

5 hours later, we still did not have the sail down. We tried various lines, twisting this way and that, manually inside gybing the sail, adding additional safety lines for the clew and tack so as to keep some control of the sail – but there was too much pressure and force. The sail seemed to have a mind of its own – just when we’d be two or three wraps from getting it free, it would find another way to get tangled. We even flew it like a symmetric spinnaker for a while, to then try to twist it on itself and at least get it furled.

We paused a couple times during this battle, for drinks of water and to re-group. I could see that the crew was getting tired. The sea state was challenging and they were constantly needing to be aware of where they were on deck and of the flailing sail, each looking out for each other and reminding – be careful with the load on this line, get low, etc. At one point the main sheet got tangled around our Thales satellite dish on the cabin top and Lauren had to quickly scramble up and free it.

It was getting dark – and time to secure the sail as best we could. I didn’t want there to be an error chain. One problem that develops into another that leads to something else. A situation can quickly deteriorate like that and being 1000 miles from help is not a good place for that to happen. We discussed some options and I made the call – let’s get the spinnaker wrapped around the forestay, secure it with sail ties as best we could, and get some rest. None of us had eaten lunch either – we needed to refuel our bodies and relook at the problem, to come up with some new options for daylight.

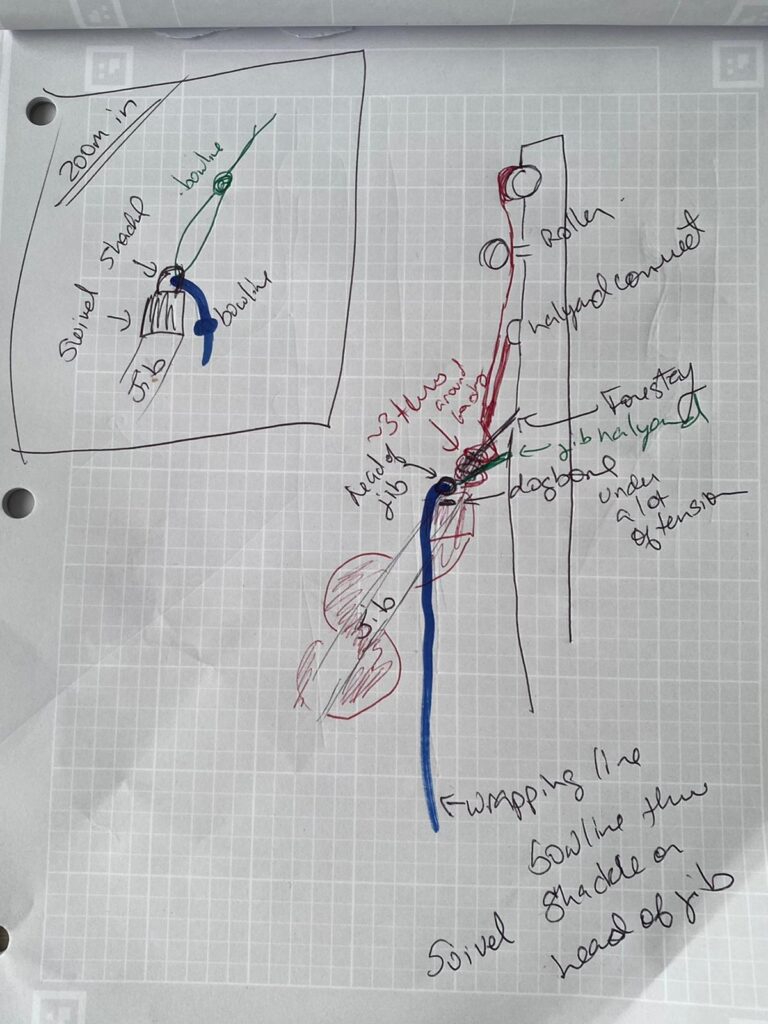

Within all the negatives, I found some positives. The crew was working well together, communicating, even joking at some points. There was no giving up. Everyone still had new ideas on ways to resolve the problem. It became clear that someone was going to have to climb the mast to either untangle the sail or drop another line down, so we could better secure the spinnaker. Over a dinner of freeze dried meals – our first as a full crew – we hatched plans. A modified watch schedule was put in place over night so everyone could get some rest and Emily wouldn’t have to stand watch, as she would be the one going up the mast. We gathered supplies for her – harness, bosuns chair, GoPro in case she needed to show us something while up there, extendable mirror, long lines, and got the headsets recharged. I drew her a diagram of the top of the mast, so she would know what to look for when she got up there. We had her practice going aloft at the dock before we left Florida, something I am grateful that we did.

The four remaining crew started our watch schedule – 1 hour on, 3 hours off. The auto-pilot had started to behave again, so I thought – this will be easy, we’re far away from any other vessels, and there shouldn’t be any squalls tonight. Everyone went to bed while Lauren sat at the helm, and we began the night.

After she woke me and let me know about the auto pilot, the spinnaker, and the bird, I got a few extra layers on and came back on deck. The bird stayed in its corner and I hoped it wouldn’t get below deck or make a mess on the cushions. But I couldn’t focus on that – the spinnaker getting loose was the first problem to resolve. Lauren went to wake Rudy and Greg and they wrestled with the pieces of sail that had come loose, this time in the dark, always with life vests on and tethers attached. They got the bottom of the sail wrapped up again, but the top still flapped annoyingly in the wind. We resumed the watch schedule, each taking a turn at the helm. When my next shift came, I sent Lauren back for a 30 minute nap and sat at the helm, hand steering the boat, and continued plotting our next moves for when it became light.

Always at the top of my mind is safety. No one wants to arrive in a port with a visual reminder of what has gone wrong but the safety of the crew and vessel far outweighs any hits to my pride. I was proud of the way we carefully worked each problem as it arose. Of course I looked back and played the what if game – what if we had raised the sock again, instead of working on the knot? What if I had decided to lower the spinnaker sooner? What if I had gotten more crew up to start? These are things I may consider in the future, but the only path forward now is to continue to manage the situation in a calm manner, using the collective knowledge on board to get to port.

Lauren came back on deck at 0330 ET, when it starts to get light out here, two time zones away. She went to wake the rest of the crew. Everyone assembled, quickly ate a bowl of cereal, and as they came on deck, I took the opportunity to check in, individually. How rested were they? What was their mindset? Did they agree with my plan A and plan B? Everyone was ready to support Emily going aloft, with the main goal of getting a line attached up there, to then drop and wrap around spinnaker to secure it better. We were making good time under the main, which I had reefed in the night to reduce pressure on the person at the helm. I spoke with Emily carefully, making sure she knew that we could continue as we were – she didn’t have to go aloft if she was uncomfortable with the wind or sea state. But she was ready to go.

Greg donned the headset and tested comms with Emily. He and Rudy each controlled a line attached to Emily, as we wanted to have more than one line taking her up the mast. I stayed out of the cockpit and roamed on deck, counting the seconds until Emily would be back on deck. Lauren was on the cabin top with binoculars, spotting for Emily. Up she went to the top – and relayed back to Greg, who then relayed to me what Emily saw. The best place to attach a line would be the top of the jib. She worked herself around to the front of the mast and got the line on. She then started to make her way down the mast – when the line escaped her grasp. Of course, always another wrinkle.

It waved out tantalizingly in front of the spinnaker and then back. Lauren climbed a few steps up the mast with a boat hook and it was just beyond the reach of her 5′ 3″ height. Rudy and his 6′ 2″ frame scrambled up, and stretched. We all held our breath as the line swayed back and forth – and Rudy was able to snag it. Emily then grasped it from midway down the mast, untangled a few knots and lowered the line to Lauren, who passed it to me, and I secured it. Phew.

Greg and Rudy lowered Emily the rest of the way down the mast and I breathed a sigh of relief. Next, up: wrapping up the spinnaker. I returned to the helm and got the boat headed downwind, while Rudy, Lauren, and Greg worked together to feed this new line around the flailing spinnaker again and again. They finished 16 minutes ahead of my mental deadline to get back on our course – we also have a low pressure system behind us that we’re keeping an eye on.

Lauren relieved me and began wrestling with the helm and the following sea that had built up. I joined the other crew down below to make a new modified watch system to get through the day – everyone would take 30 minutes at a time at the helm, with 2 hours on and 3 hours off. Emily made celebratory pancakes and we all relaxed. Rudy relieved Lauren at the helm and she came down for her pancake – and suggested that I text to Laurent at Just Catamarans and Francis back in Boston about the auto-pilot, which was the next item on the problem list. Greg hadn’t seen a way to adjust the chain tension – but Laurent had a suggestion to move the motor bracket, to both align the chain sprocket with the one that is connected to the helm and to add more tension to the chain. Think of it like a bike chain going between a front and a back wheel.

I went down for a much needed nap and when I woke up for my next watch, Greg adjusted the auto-pilot. Much to the delight of everyone who had taken a turn at the helm this morning – it seems to have worked!

Perhaps the most important thing I learned from this adventure is chose who you sail with well and while having a chain of command is important, also let the crew show their strengths. Watching them work on the foredeck was amazing. I will sail with them anywhere. When I introduced the crew to one another I said of Rudy “I trust him with my life”. That is now true of the entire crew.

Safety is #1 and I am proud that we came through unscathed. As we were doing safety briefings I kept saying: “when a situation arises, don’t panic, take a breath”. We did that during each problem over the past couple days. One could also see the value gained by sitting with a bottle of water and chatting as part of the resolution process.

I would not consider this a failure. It’s disappointing in the moment and will require additional work to get resolved, which will be a challenge with our schedule and in a foreign port. But witnessing the strength of our crew and the lessons learned far outweigh the negatives. I’m proud of how we faced the challenge and have confidence in overcoming whatever the ocean throws at us next.

Oh, and no sign of that bird.

Well done sticking with it. No ocean crossing us without its challenges.

Here’s a little known tip for when the spinnaker wraps around the forestay: gybe the main and it will reverse the vortex that wrapped the kite and unwrap it using the wind. Best to do it quickly. Once the knot is set, well, you know how that goes.

It didn’t sound easy Phil. It certainly seems more than what your crew is capable of, but also who they are. Great work people!

Great teamwork! Going up the mast out at sea is intimidating!

Wishing you less excitement for the rest of the journey.

Great work all together. Hope you can be more relaxed on the last stretch of the voyage. Happy to hear you are all safe and kudos to everyone but especialle to Emily climbing up the mast.